3 Accounting

3.3 Capital Assets

3.3.10 Capital Asset Accounting

3.3.10.10 Recording

Once the capital asset system is in operation, the government needs to make sure that assets which should be capitalized are properly recorded and that records are brought up to date when assets are disposed of or replaced.

3.3.10.20 Determining ownership of capital assets

While assets may be jointly acquired, constructed or used, an asset can only be asserted to be owned by one government and therefore may only be reported as such on one set of financial statements. Generally, the government that owns the asset and holds the title determines who should report the asset even if used or paid for by someone else. For example, a city pays to construct a park on port property. The port owns the land and as such, should report the asset. However, when a title is not available, it may be difficult to determine who owns the asset. In such cases, the party responsible for managing and maintaining the asset should be considered the owner and report it. In the previous example, even if the city assumed responsibility for maintaining the park, the port would report the asset since they own the land. However, there is a potential for the city to report a leased asset if there is a lease agreement in place for the park.

Whenever there is a question about ownership or the correct classification or reporting of an asset that was acquired, constructed or used jointly, the government should check with the other parties involved to ensure consistency in reporting the asset and clarify any applicable contracts or agreements as needed.

3.3.10.30 Cost to be recorded

Original cost (historical cost) is the amount spent to acquire an asset. This cost is based on the actual price paid, including related taxes, commissions, installation costs and any other costs related to acquiring the asset or preparing the asset for use. Costs should only be capitalized when directly attributable to a specific asset. As such, costs related to studies that determine feasibility or the best location of an asset should not be capitalized. On the other hand, legal, engineering, architectural and other ancillary fees related to acquiring, or putting in service, a specific piece of property could be capitalized.

Land costs typically include: the purchase price; closing costs, such as title to the land, attorney fees, and recording fees; assumptions of any liens, mortgages, or encumbrances on the property; costs incurred in getting the land in condition for its intended use, such as excavation, grading, filling, draining, clearing, removal, relocation or reconstruction of property of others; retaining walls; parking lots; fencing; landscaping; and any additional land improvements. Any proceeds obtained in the process of getting the land ready for its intended use, such as salvage receipts on the demolition of an old building or the sale of cleared timber, should be treated as a reduction in the price of the land.

The actual price should approximate fair market value. If the information regarding original cost is not available, the government needs to estimate the original cost. This cost principle applies to both governmental and proprietary capital asset acquisitions.

3.3.10.40 Additional cost considerations

Costs that do not add to the utility of an asset should not be capitalized. For example, expenditure to repair a piece of equipment that was damaged during shipment should be expensed. In addition, training on how to use a newly acquired asset should not be capitalized as it would not meet the criteria of a necessary cost to place the asset into service.

Costs clearly related to the acquisition or construction of capital assets that are shared across more than one capital project, should be capitalized. These costs should be allocated to the individual projects.

Each capital asset purchase should be analyzed carefully to determine which portions of the cost should be capitalized.

Specific guidance on this topic may be provided in industry publications or mandated by certain regulatory agencies. For example, FERC guidance for PUDs, provides that any amounts incurred for plant additions that are in excess of just and reasonable charges should be expensed. Likewise, if excess costs are incurred to replace individual units of property damaged in a storm so as to restore the utility system to operating condition without delay, then only the normal or fair cost is charged to plant, the balance to maintenance.

3.3.10.60 Donated and contributed assets

Assets are sometimes donated to a government. Donations of cash to be used to purchase or construct a specific asset should be reported as revenue (In governmental funds: BARS 331/333/334, Federal Direct Awards/Federal Indirect Awards/State Awards; BARS 337, Local Grants, Entitlements, Tribal Government Distributions, and other payments; or BARS 367, Contribution and Donations from Nongovernmental Sources. In proprietary funds: BARS 374/379, Capital Contributions.).

Contributed capital assets intended to be used in operations should be reported at the acquisition value plus any applicable ancillary charges. Acquisition value is the price that would be paid to acquire an asset with equivalent service potential in an orderly market transaction at the acquisition date, or the amount at which a liability could be liquidated with the counterparty at the acquisition date. Contributed capital assets intended to be sold should be reported at fair value.

3.3.10.61 Transferred assets

Assets are sometimes transferred within a government and between governments. Capital assets transferred between funds or between financial reporting entity components should be transferred at their current carrying value, both the original cost and accumulated depreciation amounts will transfer. For additional information, see Governmental Accounting Standard Board (GASB) Codification of Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards Section S20— “Sales and Pledges of Receivables and Future Revenues and Intra-Entity Transfers of Assets and Future Revenues” or Codification of Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards (Cod.) Section (Sec.) Co10— “Combinations and Disposals of Operations”

Assets transferred between governments that qualify as a transfer of operations (such as with annexations) should be accounted for and valued consistent with guidance in GASB Cod. Sec. Co10. For example, the transfer of assets relating to an annexation should be recorded at the carrying value of the transferor (the government giving up the assets). Annexations are considered a transfer of operations. In addition, such transfers are reported as a special item.

3.3.10.65 Acquisition of another entity or its operations and government mergers

Government acquisitions are transactions in which a government acquires another entity, or its operations, in exchange for significant consideration. In this case, assets acquired (and liabilities assumed) are required to be measured based on acquisition values.

A government merger includes combinations of legally separate entities without the exchange of significant consideration. In this scenario, the use of carrying values should be used to measure the assets and liabilities.

For reporting requirements, see GASB Cod. Sec. Co10 for further details.

3.3.10.70 Works of art and historical treasures

Works of art, historical treasures, and similar assets are considered to be capital assets and as such they should be capitalized at their historical cost if purchased or acquisition value if donated.

Exhaustible assets (such as exhibits whose useful lives are diminished by display or educational or research applications) should be depreciated over their estimated useful lives. Governments should not depreciate collections or items considered inexhaustible (i.e., the individual works of art or historical treasures that have extraordinarily long useful lives). Distinctions of exhaustible and inexhaustible items or collections, or their useful lives need to be made by each government.

For reporting requirements, see GASB Cod. Sec. 1400 for further details.

3.3.10.80 Improvements, repairs and maintenance

Costs relating to an existing asset need to be carefully evaluated as they are incurred to determine whether they should be expensed or capitalized. This evaluation will depend on the nature of the cost as well as the government’s policy.

Routine repair and maintenance costs should be expensed as they are incurred.

Costs that represent betterments, such as those that increase service capacity or efficiency should be capitalized. For example, an example of an increase in service capacity is a road that is widened to include another lane. An example of an increase in efficiency might be the ability to raise the speed limit of a road due to the addition of entrance or exit ramps. To the extent that a project is partially a betterment, the amount of the betterment should be estimated and capitalized.

Costs that extend useful life should also be capitalized. For example, a road that is fully depreciated undergoes a significant reconstruction. The costs of the reconstruction should be capitalized.

For major maintenance or replacements of components of a pre-existing asset, there are several approaches that might be used. Local governments should determine in advance what approach(s) will be used, address the approach(s) to be used in its policy, and then apply it consistently.

- Componentization. This allows for recording key components as separate asset records and depreciating over respective useful lives. See BARS section 3.3.10.150 for more information. For example, if the roof is recorded as its own component, then the old asset record would be removed and the new asset record added.

- Expense the replacement or major maintenance. This approach is recommended when using group or composite depreciation as assets are part of a pool and no longer have individual identity.

- Adjust the existing asset record for the addition and the removal. Capitalize subsequent replacements or major maintenance (such as a new roof) and adjust the existing asset record (and accumulated depreciation) for the removal or disposal (such as of the old roof). A gain or loss on the disposal should be recognized, unless the composite/group depreciation method is used. The local government’s policy should address how the original costs will be determined when the existing asset record is updated for the replacement.

If the modified approach is used, different guidance applies to improvements, see BARS section 3.3.10.145.

3.3.10.90 Date placed in service

Capital assets should be depreciated over their useful lives. Purchased or acquired assets are presumed to be useful upon receipt and therefore recorded as “placed in service” for accounting purposes. Constructed assets should be re-classified from construction in progress and begin to be depreciated when they are substantially completed or otherwise available for use. Construction in progress reflects the status of construction activities of buildings, other structures, infrastructure, etc. Construction in progress is a non-depreciable capital asset since the asset’s useful life has not yet begun.

Local governments should use professional judgement to determine the timing of the transition from construction in progress to a depreciable capital asset. An asset would be considered substantially completed when it can at least partially perform its intended function. For example, an empty building for which the government obtained the occupancy permit, or a structure that is completed except for the landscaping, or equipment that was delivered but has not yet been tested, configured or assigned would all be considered substantially complete – these are available for use even though the government is not actively using them. A multilane road with cars using some of the lanes, a partially constructed building, or an asset that is being used even if not all “punch list” items are completed would similarly be considered substantially complete – these assets are available for use, even though use may be limited or subject to additional capitalizable improvement.

3.3.10.100 Depreciation

Most capital assets, including infrastructure should be depreciated. There are some exceptions to depreciation for assets such as land and art and historical treasures, if those assets are inexhaustible. In addition, an asset that has been surplused or that is held for possible future use is an investment and should not be depreciated. For quarries, timberlands, and mineral rights, depletion expenses must be recorded. Since properly maintained infrastructure assets have the potential of indefinite useful lives, there is an option of not applying depreciation for infrastructure assets that meet certain criteria as defined in Governmental Accounting Standard Board (GASB) Codification of Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting Standards (Cod.) Section (Sec.) 1400— “Reporting Capital Assets”; this is referred to as the modified approach.

The objective of depreciation is to spread the costs of capital assets incurred in one period equitably over multiple periods for which the capital asset will benefit. Several items should be considered when depreciating assets, as discussed below.

3.3.10.105 Unit of depreciation

Governments may depreciate by class of assets, by a network of assets (such as a road network), a subsystem of a network (such as residential roads, arterial roads, or highway), or by individual assets. The government’s policy should prescribe how assets will be depreciated. Also, regardless of how assets are depreciated, sufficient information and support should be retained to identify them and support their existence.

3.3.10.110 Salvage value

Salvage value is the estimated fair value of a capital asset, infrastructure or otherwise, remaining at the conclusion of its estimated useful life – after considering the cost of demolition or removal. In most cases, it is probable that many infrastructure assets will have no salvage value, given the cost of demolition or removal. For other asset types, salvage value is typically expected to be trivial and if so, can be ignored in establishing the amount to depreciate. However, if scrap or sale proceeds are expected upon disposal and these proceeds exceed the cost of demolition or removal, then this value can and should be factored into the depreciation calculation.

3.3.10.120 Estimated useful life

Depreciation must be based on a reasonable estimate of expected useful life or service life; that is, the number of years, miles, service hours, etc., that the government expects to use that asset in operations. Service life means the time between the date the asset is includible as an asset in service to the date of its retirement.

Ideally, governments should base useful life estimates on its actual experience and plans. For example, internal sources of information about useful life might include property replacement policies or practices, property disposal information, and budgeting information regarding the planned timing for replacement of assets.

However, if this information is not available, the government can look to industry guidelines for a starting estimate and then revise the estimate as additional information becomes known. The use of another’s estimate should also be adjusted for differences in application, quality, environment, and maintenance practices that may vary amongst the entities.

The useful estimate should consider:

- Present condition;

- Expected future use, including anticipated changes in future usage rates or patterns; as well as how long it is expected to meet service and technology demands;

- The government’s own experience;

- Construction type or quality;

- Maintenance policy;

- The government’s historical experience with assets of this type as well as any industry, manufacturer or regulatory guidelines on the life-expectancy of the asset;

- Any legal, regulatory, or contractual provisions that might affect the estimate for an intangible asset.

Governments should maintain support for their useful life estimates as long as they are in use in order to demonstrate how the estimate was determined. Some examples of support might include engineering or depreciation studies.

Depreciation is intended to allocate the cost of a capital asset over its entire useful life to the periods that are benefitted. As useful lives are an estimate, periodically, local governments should consider information available about the existing estimates and make adjustments as needed. For example, governments should evaluate the service life of assets that are replaced or disposed to assess whether useful life estimates for the related class should be updated. Adjustments should be made prospectively to useful life and depreciation expense to ensure costs are allocated up to the end of its service life.

Estimates involving dissimilar assets that are depreciated together (such as using the composite depreciation method) should be evaluated more frequently than other useful life estimates due to the risk that the makeup of the group may change over time.

3.3.10.130 Fully-depreciated assets

If a government has fully depreciated assets, they should continue to report them until they are disposed of, sold, or replaced. However, fully depreciated assets that are still in use might be a red flag that useful lives are not reasonably accurate. The process of periodically evaluating and adjusting useful lives should prevent a material amount of fully depreciated assets from being reported but still in use. In practice, there are two legitimate reasons there may be fully depreciated assets that are still in use:

(1) The use of average estimated useful lives for entire classes of assets means that at least a few fully depreciated capital assets typically will be reported (i.e., those whose actual lives exceed the group estimate). This is acceptable, but only if such balances do not become material, in which case the estimated useful life for the group would likely need to be changed.

(2) For assets that have multiple components with different useful lives (such as a building) but are recorded and depreciated as one asset record, there might be a composite rate used that might reflects the service life of different components (such as a use of a weighted average). This practice results in accelerated depreciation and the overall building asset may be fully depreciated but still in use.

3.3.10.135 Accounting for fully depreciated assets

As noted above, a significant amount of fully depreciated assets indicates that the useful lives were not appropriate. If a correction needs to be made to reflect the accurate useful lives of the assets, follow these steps:

(1) Create a new estimate for useful life

(2) Calculate the depreciation schedule from the beginning of the asset with the new useful life

(3) Determine what year each asset is in under the new depreciation schedule

(4) Compare the currently reported accumulated depreciation to the amount calculated under the new depreciation schedule.

(5) The difference in the two amounts would be reported as an error correction

There should also be a note disclosure that discusses the error correction.

3.3.10.140 Depreciation methods

There are two primary depreciation methods used by local governments in practice: straight-line or group life.

Straight-line depreciation

Straight-line depreciation is the most common method used. With the straight-line method, the cost of an individual capital asset (less any salvage value) is allocated equally over its estimated useful life.

Group or composite depreciation

Group or composite depreciation should only be used in appropriate circumstances, and should be supported by rationale documented in the capital asset policy.

In group depreciation, similar assets are depreciated as one record, such as a fleet of police cars or lane miles of pavement of a road. It is applied when it does not make practical sense to record and depreciate assets on an individual basis. Composite depreciation is used for dissimilar assets such as for depreciating all the roads and bridges of a state.

This depreciation method cannot be applied across different classes of assets (such as furniture and vehicles) and must not interfere with depreciation being charged to the appropriate functional expense in governmental activities (such as one cannot depreciate public safety assets and culture/recreation assets together in one group).

The accounting methodology is the same for both methods. The group of assets should be treated as a single asset; a depreciation rate determined based on the average life of the group (can be a weighted average, simple average, or based on an assessment). The depreciation rate is applied to the asset costs each year. Disposals are recognized by adjusting the asset record and accumulated depreciation (with no gain or loss typically recognized except in unusual situations). Governments using this method should be able to identify the assets using other source records such as operational records. When some items within the group are retired, the cost of the items is removed from both the asset and the accumulated depreciation account and no gain or loss is recognized. Depreciation continues to be charged only for the remaining assets at the original rate. The gain or loss is deferred until the entire asset group is disposed of, at which point it would be recognized.

When depreciation charges are based on time periods, charges should be made for each month that an asset is in service. Exceptions such as the half-year convention or excluding depreciation in the first year of service are acceptable, unless this practice results in material distortions in operating income. This might occur when capital asset additions to a fund in any one year are very large. When such large additions are done, depreciation must be charged for no less than each whole month the additions are in service, because it is likely that material distortions in operating income would result from applying more approximate methods.

3.3.10.145 Modified approach

The modified approach is an alternative to depreciating certain infrastructure. Governments make a commitment to maintain the infrastructure at a certain level and therefore, do not depreciate the assets. All maintenance and preservation costs are expensed, regardless of whether they extend useful life. The only costs capitalized are those related to betterments or entirely new additions that did not previously exist. Replacement of a pre-existing asset, such as a bridge, would be expensed as a preservation cost unless there was a portion of the project that was a betterment – such as the new bridge added another lane. Those using the modified approach should ensure they meet all applicable requirements for using this method.

3.3.10.150 Componentization of assets

Componentization involves identifying and separately recording asset components that have different useful lives and depreciating them over their respective useful lives; rather than recording a composite asset as one asset record. For example, a building is a composite asset because it consists of many components such as a foundation, roof, heating and cooling system, and electrical system that might have different useful lives. A road could also be considered a composite asset due to the surface layer and the base/sub-base having different useful lives.

Componentization is a preferred method because it more accurately allocates depreciation over the periods benefitted than use of a composite rate. The decision to componentize assets of different types should be addressed in the government’s policy and be consistently applied. It is preferable to begin componentization at the time an asset is constructed or purchased. The costs of the composite asset should be reasonably allocated to the various components.

3.3.10.160 Depreciation on donated assets

Depreciation of assets acquired from contributions is calculated in the same manner as for other assets.

3.3.10.170 Capital asset impairment

GASB Cod. Sec. 1400 portion on Impairment of Capital Assets requires the immediate recognition of decreases in the productive capacity of capital assets that are expected to remain in service, even if there is no change in the estimated useful life of the asset. It does not apply to assets reported using the modified approach.

The Statement identifies five indicators of possible impairment:

1. Evidence of physical damage – such as an office building damaged in a storm;

2. Changes in legal or environmental factors – such as an underground storage tank that is no longer usable due to changes in environmental standards;

3. Technological changes or obsolescence – such as medical equipment that still can be used, but for which the demand is expected to significantly decrease with the advent of more attractive treatment options;

4. Changes in manner or duration of use – such as a school building being used as a warehouse;

5. Construction stoppage – legal or practical reasons may cause to abandon a construction project, such as a road construction that threatens the habitat of endangered species).

The presence of one of these indicators does not automatically prove that the impairment has occurred. For example, the alternative use of capital asset could have the same value as its original use. The presence of an indicator, however, does put management on notice that it needs to consider the possibility that an impairment may have occurred.

Only permanent impairments of capital assets should be recognized in the financial statements. If a government recognizes impairment because it cannot determine that the situation is only temporary, it may not recognize a subsequent recovery in value should the impairment ultimately prove to be temporary.

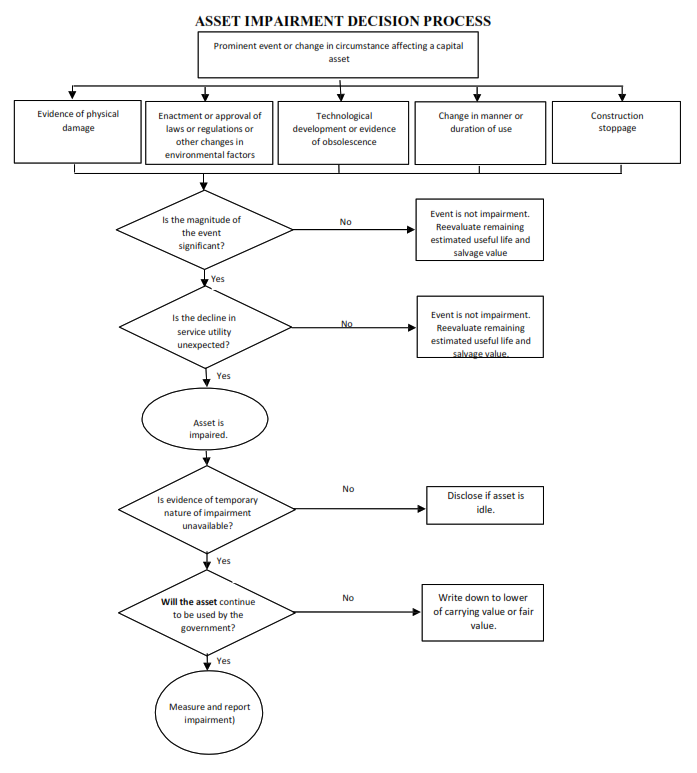

The following flowchart is designed to help the governments determine if there is a need to calculate and disclose the assets impairment.

3.3.10.180 Calculating capital asset impairment

For permanently impaired assets, the appropriate accounting and financial reporting depends on whether the asset is expected to remain in service. For capital assets expected to remain in service, the impairment loss must be recognized according to methods prescribed in codification.

3.3.10.190 Reporting

In some cases, capital asset impairment will qualify as an extraordinary item. Capital asset impairments subject to management control (e.g., change in manner or duration of use) may qualify as special items. Otherwise, capital assets impairment should be treated as an element of net program cost in the appropriate functional category.

The notes to financial statements should disclose the amount and classification of impairment losses not visible on the face of financial statements. Also, any capital assets that are idle either permanently or temporarily as a result of impairments, should be disclosed.

All insurance recoveries, including those not associated with the impairment of capital assets, should be reported net of the related loss as soon as the recovery is either realized or realizable.